Science and Fiction in “The Birds” and The Blob Bloom: Lessons Learned from a Potential Toxic Algae Eco-apocalypse

After trying mountain biking, fishing, skiing, and golfing, my Marine Corps officer, southern Californian dad attempted to get the entire family interested in surfing. On another early Saturday morning, my parents, brother, and I piled in the car and drove fifteen minutes from our home to Doheny State Beach, a popular spot for beginner surfers and young families in Dana Point, California. Shortly after he managed to outfit me and my brother into wetsuits, I made a beeline for the tidal pools to explore, swiftly abandoning my ten-foot, bright yellow, foam longboard on the cold sand as my father shouted after me. I began wandering down the shore, hopping from tidal pool to tidal pool, with my eyes looking determinedly down in the shallow waters in pursuit of my favorite creatures from marine science camp, a purple sea star or sticky sea anemone. Suddenly, I looked up and encountered a creature much larger than what I had ever seen in any tidal pool. My body immediately froze, and I found myself glued to the sand and screamed.

“Why is it shaking?” I exclaimed while attempting to deter my eyes from the seizing sea lion just a few yards down the beach. As a mere fourth-grader, I suddenly felt confused and terrified, barely processing the scene right in front of me—these creatures were typically approachable and charismatic. Quickly stumbling through the sand towards me, my mother shielded my eyes and explained how the sea lion was sick due to the “bad algae” that made the water shades of red and brown. She made a brief phone call and soon a group of people in matching navy blue t-shirts with “The Pacific Marine Mammal Center, Laguna Beach” in large letters on the front came to take the spasming sea lion away. This left me wondering: How could algae be the cause of such a horrific scene? Safe to say, however, I never went back to marine science camp or explored tidal pools again.

***

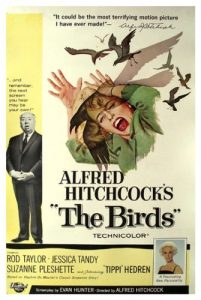

Nevertheless, many years later I rediscovered my interest in marine science while taking an oceanography class in college and subsequently seized the opportunity to study harmful algal blooms. I spent the summer in Seattle investigating the extent and toxicity of harmful alga species Pseudo-nitzschia at the NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center (NWFSC) under the mentorship Marine BioToxins Program Manager Dr. Vera L. Trainer. During this time, I made the connection between this same alga I happened to study and this dramatic childhood experience that still makes me shudder to remember. Furthermore, I surprisingly learned that major toxic algae events—similar to the sea lion seizure incident—had not only inspired my research project, but also the primary plot line in the classic horror film, Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds.

The Birds (1963) tells the story of a young woman, Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren), travelling from San Francisco to Bodega Bay, California in romantic pursuit of a handsome lawyer, Mitch Brenner (Rod Taylor). Upon Melanie’s arrival in Bodega Bay, the first sign of abnormality occurs when a seagull attacks her, followed by a mass seagull attack at Mitch’s sister’s birthday party. Soon, the entire town is under attack by flocks of aggressive seagulls, sparrows, and crows, causing a spiraling of negative effects including a gasoline fire, townsperson deaths, and widespread panic. After Melanie, Mitch, and his family are held captive in his family home by the rabid birds, Melanie is severely injured. In the final scenes, the group attempts escape in Mitch’s car while listening to a radio report describing how the military may have to intervene in the wake of the failure of the local authorities to ward of the inexplicable, deadly bird attacks in Bodega Bay.

The original movie poster for Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds[1] (left) and the front page of the Santa Cruz Sentinel from August 1961,[2] covering the event that inspired the horror film (right).

In light of the debut and popularity of The Birds, scientists have since traced the origins of the fantastical events of the film and linked them to the toxin-producing Pseudo-nitzschia australis.[3] While scientists have confirmed the connection between toxic algae and The Birds, I can only speculate the toxic algal origins of my personal experience. However, both incidents purport an eco-apocalyptic question: Could algae make the ocean waters toxic, infecting mammals (including humans) and birds causing them to become homicidal? If estimates show that the frequency of toxic algae will increase in the wake of global climate change, can this seemingly outlandish prospect become a reality?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the short answer is no. However, the recent Blob Bloom along the west coast of the U.S. serves as an example of the drastic effects the environmental phenomena, such as the changing climate and harmful algal blooms, can have on the natural environment. Plus, The Birds represents a highly negative relationship between humans and the natural environment, particularly in the context of unfamiliarity, alleged disaster, and climate change.

Harmful Algal Blooms, The Blob Bloom, and Pseudo-nitzschia

Generally, algae refers to a wide variety of aquatic organisms that conduct photosynthesis, and a bloom occurs under specific conditions that allow an algal conglomerate to reproduce and grow at an exponential rate. An algal bloom is deemed “harmful” based on an array of factors: ability to kill fish or other marine mammals, render seafood unsafe for human consumption, take the form of “unsightly” scum, or otherwise detrimentally alter the ecosystem.[4] Typically, major algal blooms appear on the surface of the given body of water as a mysterious slimy red, brown, yellow, or green top layer. Worldwide, these colorful and unpleasant harmful algal blooms have been increasing often as a result of anthropogenic forces, primarily the changing climate, eutrophication (nutrient input), and the introduction of invasive species.

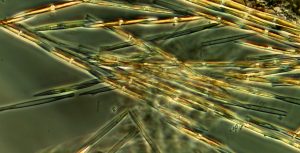

So, what was this particular “bad algae” that triggered the sea lion’s seizures, circa 2006? More than likely, it was a toxin-producing strain of the microscopic, marine, phytoplanktonic diatom Pseudo-nitzschia. Certain species of the genus Pseudo-nitzschia produce domoic acid, a neurotoxin that leads to amnesic shellfish poisoning causing gastrointestinal and neurological complications (like seizures) in humans, marine mammals, and sea birds.[5] To date, the most toxic species of Pseudo-nitzschia found on the west coast fall into one of two categories: Pseudo-nitzschia australis or Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries.[6]

A Pseudo-nitzschia “red tide” bloom off the coast of Washington state (top).[7] An image of Pseudo-nitzschia under a light microscope, magnified 1,000 times (bottom).[8]

The deadliest Pseudo-nitzschia outbreak occurred in 1987 off the Pacific coast of Canada. After eating domoic acid contaminated shellfish, four people and countless numbers of marine mammals and sea birds died. As a result, in these hotspot locations, the FDA and EPA have identified Pseudo-nitzschia and domoic acid as public health threats.[11] While over ninety-nine percent of algae are nontoxic, the prevalence of not only harmful, inconvenient algae, but also inherently toxic algae continues to increase, particularly along the west coast of the United States due to the forces of global climate change.[12] This poses a real problem. As described, these disruptive, toxic blooms have led to unprecedented economic deficit within the fishery industry, food safety risks, mass sea lion and sea bird deaths, and diagnosis of shellfish poisoning in humans.[13] While the changing climate has allowed these harmful algae species to realize and exploit new habitats, the specific environmental conditions producing toxic algal blooms remain largely unclear.The west coast runs rampant with Pseudo-nitzschia hotspots. “These hotspots are sort of like crockpots, where the algal cells can grow and get nutrients and just stew,” Trainer explained.[9] Although Pseudo-nitzschia typically accounts for less than 20% of any major bloom along the west coast between May and July, common hotspot or initiation sites for Pseudo-nitzschia—where toxic strains account for the majority of the bloom—include both Bodega Bay and Dana Point, California, the former of which acts as the setting for The Birds and the latter where I grew up surfing.[10]

The most recent major domoic acid outbreak, which prompted my study of Pseudo-nitzschia at NWFSC, took place during the spring and summer of 2015. Scientists have deemed it the largest domoic acid producing harmful algal bloom on record. Such high levels of domoic acid found in coastal waters poisoned shellfish, caused fisheries closures, and killed marine mammals and sea birds.[14] In fact, estimates suggest that the Dungeness crab fishery closures alone caused approximately $100 million-dollar loss, and some fisheries stayed closed for over a year (Fisheries of the United States, 2015). Moreover, the event was deemed a disaster when the state of California requested $138 million in “federal disaster aid” due to extensive closures of the commercial crab fisheries.[15]

Craig Welch[16] interviewed commercial fisherman Dick Ogg, who coincidentally works out of Spud Marina in Bodega Bay, California. After his moneymaking shellfish Dungeness Crab fishery closed for most of the season due to the Blob Bloom, he was essentially out of work. He and many other unemployed fishermen barely sustained their livelihoods living off a marina food bank. Often these fishermen only fished when lending a helping hand to regulators, who would test the crabs for toxins. “A lot of folks are really hurting,” said Ogg at the time.[17]

This event was deemed the “Blob Bloom” after University of Washington climate scientist Nick Bond christened the anomalously warm body of water as “the blob.”[18] Most recently, researchers hypothesize that the causes of the 2015 bloom included a variety of environmental factors, primarily abnormally warm sea-surface temperatures that increased up to 2.5˚C, presence of spring rain storms, and nutrient stress during the time leading up to the bloom.[19]

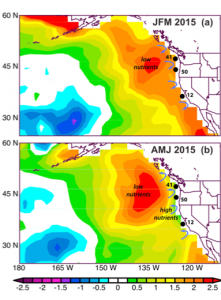

The Blob: (a) Sea surface temperature anomalies (˚C) in January, February, and March and (b) April, May, and June of 2015, relative to the 1981-2010 composite average.[20]

The Blob: (a) Sea surface temperature anomalies (˚C) in January, February, and March and (b) April, May, and June of 2015, relative to the 1981-2010 composite average.[20]

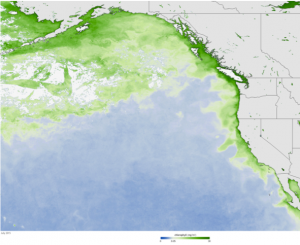

The Blob Bloom: spanning between the Aleutian Islands of Alaska to Baja California, represented via satellite-based estimate of ocean plant growth in July 2015.[21]

The Blob Bloom: spanning between the Aleutian Islands of Alaska to Baja California, represented via satellite-based estimate of ocean plant growth in July 2015.[21]

So, what is being done about these disastrous blooms? What can we do to mitigate them and help the general public gain a greater understanding of them? Oceanographers, marine biologists, and local non-profit organization alike have studied the Blob Bloom extensively in hopes of developing answers to these questions and applying solutions to future harmful algal bloom events. Thus far, the most effective method to deal with these toxic blooms remains to create monitoring and forecasting systems as well as identify the origin species and strains of algae causing the toxin production. Thanks to the efforts of various specialists, many people native to the west coast have increased awareness of the negative consequences of a domoic acid event after the Blob Bloom.

Again, the first warning signs of the extent of the Blob Bloom were a seizure-wracked sea lions and sea birds. Soon after these occurrences, scientists tested the waters to find a high abundance of Pseudo-nitzschia australis off the coast. “When I heard about that sea lion [off the coast of Washington state] and its symptoms, I thought, ‘That’s it, there’s something big happening offshore,’” said Trainer.[22] Dr. Vera Trainer has dedicated her life to the study of Pseudo-nitzschia. Over the years and under her leadership, the Marine Biotoxins team at NWFSC have augmented the global toxic algae network and mentored students, such as myself, and engendered interest and awareness of harmful algal blooms. And her favorite Pseudo-nitzschia fun fact, you ask? Her favorite algae’s appearance in pop culture: cult favorite horror film The Birds.

The Birds, Horror movies, and the natural environment

In the film after birds attacked a group of school children, Melanie and a group of townspeople discuss the event in a local diner across town. “Birds are not aggressive creatures, miss. They bring beauty into the world. It is mankind, rather, who insists upon making it difficult for life to exist on this planet,” says a woman, who is conveniently an ornithologist.[23]

“It’s the end of the world!” exclaims the drunken man at the bar.[24]

Unwittingly, the iconic 1960s horror film depicts and hyperbolizes the negative effects of a toxic Pseudo-nitzschia outbreak, creating an eco-apocalypse. By crafting this eco-apocalyptic scenario, Hitchcock portrays a highly negative relationship between humanity and nature; a relationship marked by apparent unpredictability, fear, confusion, and violence.[25] Among the most widely-acclaimed first wave of environmental apocalypse and disaster films, it introduced and contributed to an ever-growing genre that includes Jaws (1975), Cujo (1983), Komodo (1999), The Thaw (2009), and The Bay (2012). These films all have a common theme: the representation of nature and its creatures as “monsters” wreaking havoc on humanity.[26]

Memorable images from the film The Birds include school children being attacked by crows,[27] and seagulls causing a gasoline fire.[28]

Memorable images from the film The Birds include school children being attacked by crows,[27] and seagulls causing a gasoline fire.[28]

This genre relies on the mutation of either an extraordinary creature—such as a shark or giant lizard—or everyday creature—like a dog, squirrel, or bird—transforming the natural to enigmatically unnatural or even “supernatural.”[29] Clearly, The Birds (1963) relies on the everyday variety turned “uncanny” or evil in a small, insignificant coastal town in northern California. Hitchcock said, “I think if the story had involved vultures, or birds of prey, I might not have wanted it. The basic appeal to me is that it had to do with ordinary, everyday birds.”[30]

Truly, I was afraid of the natural and specifically marine environment after witnessing a seizure-wracked sea lion at a formative age. Similarly, I became more cautious of birds after watching this film.[31]* Furthermore, the two responses to the news of the bird attack on school children in the film represent the dichotomy between environmental awareness and a lack thereof. What is anyone to do when confronted with a threat that has no apparent or decipherable rationalization? Panic. Fight or flight. This tendency explains this particular horror film plot trope. In the end, the film offers no solution to the rabid bird crisis, implying humans are powerless to this natural phenomenon.

When a natural or environmental phenomenon occupies the role of “pervasive force of evil”[32] as they do in The Birds, it reinforces the original dichotomy between environmental awareness and a lack thereof, which is fueled by fear of the unknown. Unfortunately, this fear does not often prompt people to want to know more about the environment or explain the environmental disaster, just like when I stopped going to marine science camp growing up or how scientists did not investigate the origin of the real-life events that inspired The Birds until decades later. This lack of environmental awareness can have the effect of “othering” the environment—that is, seeing the environment as other and separate from humanity. If humans are not part of their natural environment, then it seems okay to degrade it. It is not me; it is other.

Overall, it remains important in the face of the increasing frequency of natural disaster—seizing sea lions or birds, the Blob Bloom, Hurricanes Harvey and Irma—not to think of the environment as other, because othering is not a call to action, understanding, or problem-solving. All in all, you probably will not have to flee your family home like Mitch and Melanie. There is probably a real explanation, and possibly solution, for the reason birds exhibit aggressive behavior and begin falling out of the sky or why the entire Pacific coastline has become toxic; therefore, there’s little reason to conceive it as other.

Notes

* Side note and fun fact: Studies have shown that crows, which are highly territorial, actually have facial recognition. This means if they see you encroaching on their territory, they will also recognize you whenever they see you next. (Think: the next time you go to work and park by that tree.) So, if a crow is attacking you, it is likely personal.

[1] “Amazon.com: The Birds Movie Poster Alfred Hitchcock: Prints: Posters & Prints,” accessed March 2, 2018, https://www.amazon.com/Birds-Movie-Poster-Alfred-Hitchcock/dp/B001T8GNBM.

[2] Sibel Bargu et al., “Mystery behind Hitchcock’s Birds,” Nature Geoscience 5, no. 1 (January 2012): 2–3, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1360.

[3] Rosie Mestel, “Hitch’s Birds Deranged by Dodgy Anchovies,” New Scientist 147 (July 22, 1995): 6–6.

[4] Patricia M. Glibert et al., “Vulnerability of Coastal Ecosystems to Changes in Harmful Algal Bloom Distribution in Response to Climate Change: Projections Based on Model Analysis,” Global Change Biology 20, no. 12 (December 2014): 3845–58, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12662.

[5] Vera L. Trainer et al., “Pseudo-Nitzschia Physiological Ecology, Phylogeny, Toxicity, Monitoring and Impacts on Ecosystem Health,” Harmful Algae 14 (February 2012): 271–300, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2011.10.025; S. Morgaine McKibben et al., “Climatic Regulation of the Neurotoxin Domoic Acid,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, no. 2 (January 10, 2017): 239–44, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606798114.

[6] McKibben et al., “Climatic Regulation of the Neurotoxin Domoic Acid.”

[7] Kate S. Zalzal, “A New — and More Toxic — Normal? Harmful Algal Blooms Find New Habitats in Changing Oceans,” EARTH Magazine, January 13, 2017, https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/new-and-more-toxic-normal-harmful-algal-blooms-find-new-habitats-changing-oceans.

[8] Image courtesy of the Marine Biotoxin program at NOAA NWFSC.

[9] Sandi Doughton, “Toxic Algae Bloom Might Be Largest Ever,” The Seattle Times, June 15, 2015, https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/health/toxic-algae-bloom-might-be-largest-ever/.

[10] McKibben et al., “Climatic Regulation of the Neurotoxin Domoic Acid”; California Dept of Public Health Environmental Management Branch Marine Biotoxin Monitoring Program, “Monthly Marine Biotoxin Report,” Monthly Marine Biotoxin Report, no. 13–13 (March 2013): 1–6.

[11] McKibben et al., “Climatic Regulation of the Neurotoxin Domoic Acid.”

[12] McKibben et al.

[13] Trainer et al., “Pseudo-Nitzschia Physiological Ecology, Phylogeny, Toxicity, Monitoring and Impacts on Ecosystem Health.”

[14] McKibben et al., “Climatic Regulation of the Neurotoxin Domoic Acid”; Kate S. Zalzal, “A New — and More Toxic — Normal?”

[15] Kate S. Zalzal, “A New — and More Toxic — Normal?”

[16] Craig Welch, “The Blob That Cooked the Pacific,” National Geographic Magazine, August 9, 2016, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/warm-water-pacific-coast-algae-nino/.

[17] Craig Welch.

[18] Ryan M. McCabe et al., “An Unprecedented Coastwide Toxic Algal Bloom Linked to Anomalous Ocean Conditions,” Geophysical Research Letters 43, no. 19 (October 16, 2016): 2016GL070023, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL070023.

[19] McCabe et al.; Xiuning Du et al., “Initiation and Development of a Toxic and Persistent Pseudo-Nitzschia Bloom off the Oregon Coast in Spring/Summer 2015,” PLoS ONE 11, no. 10 (October 12, 2016): 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163977.

[20] McCabe et al., “An Unprecedented Coastwide Toxic Algal Bloom Linked to Anomalous Ocean Conditions.”

[21] Tom Di Liberto, “Record-Setting Bloom of Toxic Algae in North Pacific,” NOAA Climate.gov, August 6, 2015, https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/record-setting-bloom-toxic-algae-north-pacific.

[22] Kate S. Zalzal, “A New — and More Toxic — Normal?”

[23] Alfred Hitchcock, The Birds, 1963.

[24] Alfred Hitchcock.

[25] Cynthia Freeland, “Natural Evil in the Horror Film: Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds,” in Monstrous Nature: Environment and Horror on the Big Screen (University of Nebraska Press, 2016).

[26] Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann, Monstrous Nature: Environment and Horror on the Big Screen (University of Nebraska Press, 2016), https://muse.jhu.edu/book/47643.

[27] “The Birds,” The Official Bodega Bay Area Website (blog), accessed March 2, 2018, http://www.bodegabay.com/the-birds/.

[28] Wade Wainio, “Why Hitchcock’s ‘The Birds’ Stands The Test of Time,” 1428 Elm (blog), December 27, 2016, https://1428elm.com/2016/12/27/hitchcocks-birds-stands-test-time/.

[29] Cynthia Freeland, “Natural Evil in the Horror Film: Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds.”

[30] Cynthia Freeland.

[31] Michelle Nijhuis, “Friend or Foe? Crows Never Forget a Face, It Seems,” The New York Times, August 25, 2008, sec. Science, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/26/science/26crow.html.

[32] Cynthia Freeland.

Works Cited

“Amazon.Com: The Birds Movie Poster Alfred Hitchcock: Prints: Posters & Prints.” Accessed March 2, 2018. https://www.amazon.com/Birds-Movie-Poster-Alfred-Hitchcock/dp/B001T8GNBM.

Bargu, Sibel, Mary W. Silver, Mark D. Ohman, Claudia R. Benitez-Nelson, and David L. Garrison. “Mystery behind Hitchcock’s Birds.” Nature Geoscience 5, no. 1 (January 2012): 2–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1360.

Brian Truitt. “‘Birdemic’ Swoops in with Cult-Film Abandon.” USA Today. Accessed February 22, 2018. https://ezproxy.lib.davidson.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=J0E425295214311&site=ehost-live.

California Dept of Public Health Environmental Management Branch Marine Biotoxin Monitoring Program. “Monthly Marine Biotoxin Report.” Monthly Marine Biotoxin Report, no. 13–13 (March 2013): 1–6.

Cynthia Freeland. “Natural Evil in the Horror Film: Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds.” In Monstrous Nature: Environment and Horror on the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press, 2016.

Doughton, Sandi. “Toxic Algae Bloom Might Be Largest Ever.” The Seattle Times, June 15, 2015. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/health/toxic-algae-bloom-might-be-largest-ever/.

Glibert, Patricia M., J. Icarus Allen, Yuri Artioli, Arthur Beusen, Lex Bouwman, James Harle, Robert Holmes, and Jason Holt. “Vulnerability of Coastal Ecosystems to Changes in Harmful Algal Bloom Distribution in Response to Climate Change: Projections Based on Model Analysis.” Global Change Biology 20, no. 12 (December 2014): 3845–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12662.

Hitchcock, Alfred. The Birds, 1963.

Jackson, J. Kasi. “Doomsday Ecology and Empathy for Nature: Women Scientists in ‘B’ Horror Movies.” Science Communication 33, no. 4 (December 2011): 533–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547011417893.

Kate S. Zalzal. “A New — and More Toxic — Normal? Harmful Algal Blooms Find New Habitats in Changing Oceans.” EARTH Magazine, January 13, 2017. https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/new-and-more-toxic-normal-harmful-algal-blooms-find-new-habitats-changing-oceans.

Masurczak, Pia Florence. “‘Danger Comes from Above’: The Representation of Nature in Hitchcock’s The Birds.” In The Life of Birds in Literature, edited by Marie-Luise (ed. and introd.) Egbert, 145–56. Trier, Germany: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier (WVT), 2015.

Mestel, Rosie. “Hitch’s Birds Deranged by Dodgy Anchovies.” New Scientist 147 (July 22, 1995): 6–6.

Murray, Robin L., and Joseph K. Heumann. Monstrous Nature: Environment and Horror on the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press, 2016. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/47643.

Nicklen, Paul. “The Blob That Cooked the Pacific.” National Geographic Magazine, August 9, 2016. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/warm-water-pacific-coast-algae-nino/.

Nijhuis, Michelle. “Friend or Foe? Crows Never Forget a Face, It Seems.” The New York Times, August 25, 2008, sec. Science. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/26/science/26crow.html.

Norden, Martin F. Changing Face of Evil in Film and Television. Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS: Editions Rodopi, 2007. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/davidson/detail.action?docID=556597.

Paglia, Camille. “Beauty and the Beasts.” Sight & Sound 8, no. 10 (October 1998): 65–65.

“The Birds.” The Official Bodega Bay Area Website (blog). Accessed March 2, 2018. http://www.bodegabay.com/the-birds/.

Tom Di Liberto. “Record-Setting Bloom of Toxic Algae in North Pacific.” NOAA Climate.gov, August 6, 2015. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/record-setting-bloom-toxic-algae-north-pacific.

“Top 10 Dirtiest Beaches in America,” June 29, 2011. https://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/top-10-dirtiest-beaches-in-america/.

Trainer, Vera L., Nicolaus G. Adams, Brian D. Bill, Carla M. Stehr, John C. Wekell, Peter Moeller, Mark Busman, and Dana Woodruff. “Domoic Acid Production near California Coastal Upwelling Zones, June 1998.” Limnology and Oceanography 45, no. 8 (December 1, 2000): 1818–33. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2000.45.8.1818.

Trainer, Vera L., Stephen S. Bates, Nina Lundholm, Anne E. Thessen, William P. Cochlan, Nicolaus G. Adams, and Charles G. Trick. “Pseudo-Nitzschia Physiological Ecology, Phylogeny, Toxicity, Monitoring and Impacts on Ecosystem Health.” Harmful Algae 14 (February 2012): 271–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2011.10.025.

Trainer, Vera L., Barbara M. Hickey, and Rita A. Horner. “Biological and Physical Dynamics of Domoic Acid Production off the Washington Coast.” Limnology & Oceanography 47, no. 5 (September 2002): 1438–46. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2002.47.5.1438.

“Vulnerability of Coastal Ecosystems to Changes in Harmful Algal Bloom Distribution in Response to Climate Change: Projections Based on Model Analysis,” n.d.

Wade Wainio. “Why Hitchcock’s ‘The Birds’ Stands The Test of Time.” 1428 Elm (blog), December 27, 2016. https://1428elm.com/2016/12/27/hitchcocks-birds-stands-test-time/.

Welch, Craig. “The Blob That Cooked the Pacific.” National Geographic Magazine, August 9, 2016. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2016/09/warm-water-pacific-coast-algae-nino/.

One Comment

Mike Janech

Steffaney,

A friend of mine forwarded your post. I really enjoyed your personalized account and perspective on the impact of diatom blooms. You have a real talent for writing. Keep it up.

Best,

Mike